Act 2: In Which Your Records Manager Gets Ahead of Himself, Thereby Tripping on His Own Feet

When last we checked in with the case of the unscheduled communications, your intrepid hero* had received a brief to write a memo to the City Information Management Committee explaining the “hidden costs” of email retention, and had scheduled a meeting with his boss (the City Clerk), the City CIO, and the assistant City Attorney who deals with records issues to hammer out a scheduling solution for text messages. The memo itself was easy, because the content is pretty much textbook records management best practice. You can read it here, or you can see my clever Prezi utilizing a “tip of the iceberg” visual metaphor here. (Regrettably I did not get to use this at the actual presentation because I didn’t finish it with enough time to clear it with my boss. But the information is still good!) I framed the issue in terms of time=money, specifically that employee time searching = that employee’s hourly wage x the amount of time searching for the total cost of retrieving records. Two complications did come up but were easily answered:

- We can charge back ‘reasonable’ search fees over $50 for public records requests: true, but is doing so good customer service? The City Clerk’s office is trying to push the idea of cutting through red tape to allow the public to work more easily with government, so this argument resonated, I think. Plus, of course, Wisconsin State Law prevents us from passing on redaction/review costs to the requestor, so any time spent on that because of inadequate information screening was a cost the city had to eat anyway.

- Email (and probably eventually texts) is physically managed by a SaaS provider. This kind of threw my “costs of running the server, costs of paying someone to run the server, costs of maintaining good digital preservation practices” arguments out the window, since Microsoft includes unlimited(!) email archives storage space with the package that the city purchased. I decided to leave the question of the environmental cost of storage to another day, but I was able to point out that “unlimited” really meant “unlimited until you reach an arbitrary cap, or the vendor decides to change the terms of service” (I think we’ve all had a bait-and-switch ‘unlimited’ mobile data plan…). Beyond that, if the City ever moved on to a new system, the cost of migration would suddenly bring the size of the email archives to be brought over into sharp relief.

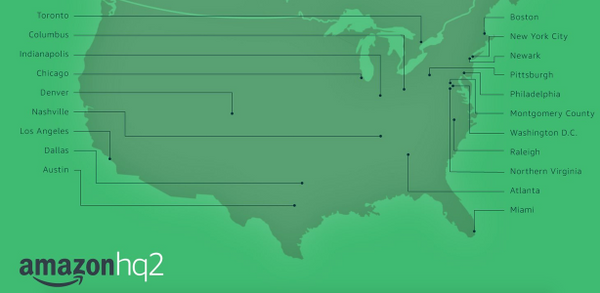

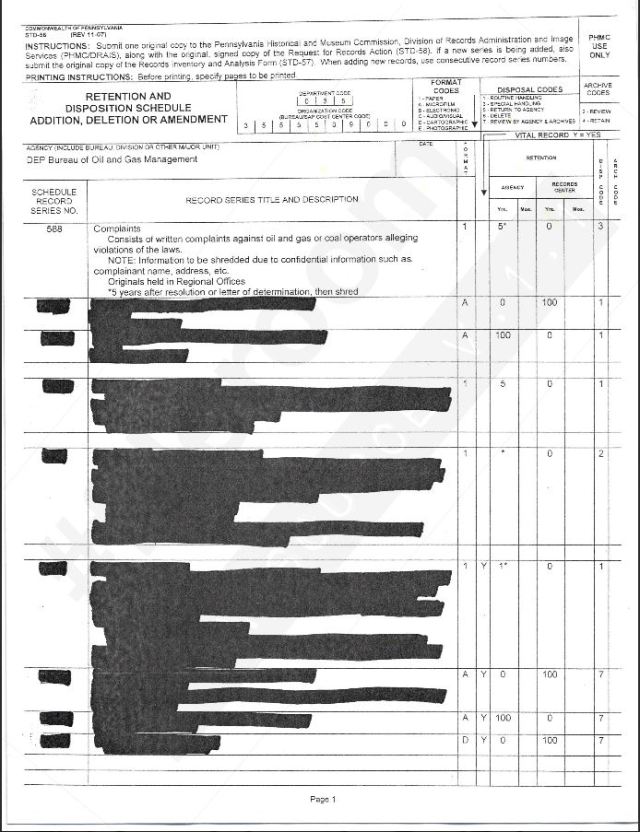

So much for the written component. Now I had to prep for the meeting and make my case for appropriate retention schedules. I did an informal environmental scan and quickly determined that some sort of two-tier retention scheme was going to be the only way to manage the vast quantity of texts and emails that would need to be addressed. Using examples from the State of Wisconsin, the newly-approved Wisconsin municipal records schedule, and NARA’s Capstone model, I put together the below chart comparing solutions, and paired that with a couple of sample schedules to bring to the meeting.  Fair enough… but once we got to the meeting, I ran into continued resistance to implementing any of my suggested solutions. IT didn’t want to get into the business of classifying texts and emails; legal was concerned about the transition from the active system to a separate archive down in City Records; my team doesn’t really have the time or skillset to review texts to the extent needed; none of us were confident that we could leave records declaration or classification to users. We decided that as a first step, we would try to submit a schedule giving all text messages a retention of 6 months, on the theory that that time period would give us time to put holds on relevant texts, but would not require us to hold onto the irrelevant ones for too long.

Fair enough… but once we got to the meeting, I ran into continued resistance to implementing any of my suggested solutions. IT didn’t want to get into the business of classifying texts and emails; legal was concerned about the transition from the active system to a separate archive down in City Records; my team doesn’t really have the time or skillset to review texts to the extent needed; none of us were confident that we could leave records declaration or classification to users. We decided that as a first step, we would try to submit a schedule giving all text messages a retention of 6 months, on the theory that that time period would give us time to put holds on relevant texts, but would not require us to hold onto the irrelevant ones for too long.

I was all set to put something together, but there was one hitch: I was asked not to include my standard disclaimer for series like this, “if a record is associated with a series governed by another schedule, retain it according to that schedule.” The consensus was that the disclaimer would be confusing to end users and would not be followed in any case, and that I should submit a straight 6 months schedule and hope for the best.

….Reader, I tried. I really did. I solicited advice from other records colleagues in Wisconsin; I asked around the Records Management Think Tank for their experience with scheduling texts under a restriction like this; I sent out requests to the RMS list and to Twitter for more policies. I couldn’t find anything that supported a *blanket* 6-month retention for all texts. As I wrestled with the language for a single schedule, I thought back to the Matthew Yglesias article about exempting email from discovery that I so thoroughly mocked on this blog lo these many years ago. If every text is retained six months, with no consideration for content, what stops people from using texts for everything, with a high likelihood that evidence of questionable texts is erased from the City logs after a certain period of time? At the same time, how can anyone possible go through all of the texts being sent by city employees to determine value? I decided at this point to play the same percentage game that NARA is playing with Capstone for emails—the significant/historically important texts, such as they are, are more likely to originate from accounts higher up in the hierarchy, so it makes sense to retain those archivally (possibly deaccessioning later through use of machine learning or similar); the rest could stay at 6 months. As such, when it came time to submit schedules, I turned in not one text schedule, but two—one for Elected Officials and Critical Staff, and one for everyone else.

Here’s your takeaway for today’s installment: do not blindside your stakeholders on schedule creation. In retrospect, I absolutely should have held on to those schedules until such time as I had a chance to consult with the relevant parties and explain to them why I thought one schedule was so problematic. I suppose I was anxious to get something through the approval process, which can take up to 6 months between City and State approval, which is why I didn’t wait, but the effect of my impatience was to anger EVERYONE involved. The CIO was annoyed because of the technical capacities that I assumed in my schedules (IT had since decided not to pursue a contract with the vendor of the solution described). The assistant city attorney was annoyed because he thought I overstated the ramifications of having only one schedule for all text messages. Everyone was annoyed because I made this change unilaterally and submitted it for approval without so much as a by-your-leave.

I own it—this was absolutely an unforced error. I 100% should not have rushed to get something/anything approved without checking in with the stakeholders about major changes. I stand by my reasoning for putting in a two-tiered schedule for text messages, and I did not withdraw the schedules at that time, but I almost certainly poisoned the well for getting the schedules actually approved by CIMC. Principles and best practices are all well and good, but they don’t do anyone any good if they alienate the people you need to sign on in support. Plus, of course, as it stands the retention of text messages is sort of the Wild West, so I’m not doing myself any favors delaying it for that reason either.

Next time (tomorrow?): Brad tries to make up for lost ground, plus the followup meeting/discussion and where we go from here.

*Possibly the first time anyone has referred to a records manager as “intrepid”. Definitely the last time.